Helen Weinstein and the team at Historyworks are currently advising English Heritage about the public understanding of the history of York Castle - including the Tower and the wider precinct of the Castle complex and more recent prison precinct - to devise and deliver public engagement with the long history of the site. To find out more about the January tours & talks which have been organized for free as HMD events - please scroll below to find the information - including a report summarizing the tours and talks from HMD 2015.

For HMD 2016 we are teaming up again with English Heritage and York City Council to lead a free walk for the community to mark Holocaust Memorial Day called 'York's Jewish History: Community and Identity Through the Centuries' on 27th January 2016, 12.30pm to 2.00pm, led together by Jeremy Ashbee (Chief Properties Curator, English Heritage) and John Oxley (City Archaeologist, City of York Council) with Professor Helen Weinstein (Director of Historyworks) and Ben Rich (Chair, York Jewish Liberal Community) see details below on this page. All Welcome!

The following pages are designed as a guide to navigating the interpretation presently offered by the organizations that have custody of the York Castle sites, (English Heritage, York Museum Trust, York City Council) adding wider histories presently not represented in these interpretations.

For example, Historyworks has focused on providing the Jewish community with the longer history of burials and fires at the site before the tragedy of 1190 and afterwards, with thumbnails of histories not presently included in the interpretation such as the archaeological evidence of the site's previous use as a Roman cemetery by the VI Legion, and the trial and execution of the Luddite political protestors in 1813.

Jewish History Walk on 27th January 2016 to mark Holocaust Memorial Day from Y01 7FR to Y01 9SA

Wednesday 27th January 2016

12.30pm to 2.00pm Holocaust Memorial Day - Walking Tour

Free - NO BOOKING REQUIRED - all welcome!

LOCATIONS: The walk starts at the steps of The Yorkshire Museum, Museum Gardens, York Y01 7FR. The walk ends at the steps of Clifford’s Tower, Tower Street, York, Y01 9SA. For those who wish to have a longer time inside Clifford's Tower or engage in further dialogue with the four speakers, we will have from 2pm to 3pm on site at Clifford's Tower for those who wish to stay beyond 2pm (weather permitting as there is little cover from the rain at this English Heritage Site). Warning: Steep steps included. Wrap up warm and ear comfortable shoes!

York Jewish History Walk: Community and Identity Through the Centuries

Please join Professor Helen Weinstein (Director, HistoryWorks) and Dr Jeremy Ashbee (Head Historic Properties Curator, English Heritage), John Oxley (City Archaeologist, City of York Council) and Ben Rich (Chair, York Jewish Liberal Congregation) who are together leading this FREE walk.

The history of the Jewish community in York is a fascinating, if often overlooked, chapter in the city’s long and colourful past. Whilst attention is usually focused on the tragic event at the site now called Clifford’s Tower, there are stories to be told about the resilience of the Medieval jewish community and of commemoration and revival of Jewish life in the more recent past. Along the walk, we will discover sites of synagogues both ancient and more recent, meet prominent Jews such as Aaron of York and the unfortunate Benedict, explore the remains of a 12th century house and the place of a significant Medieval Jewish burial ground, before finally entering the site of Clifford’s Tower itself where we will reflect on murder and remembrance at the location where Jewish families tragically died on 16th March 1190.

Please join the walk for the start meeting point at 12.30pm from the steps of The Yorkshire Museum and ends at 2.00pm at Clifford’s Tower. Sponsored by HistoryWorks and English Heritage. All participants will have FREE entry for a tour of Clifford’s Tower at the end of the walk. No booking required. Turn up on the day with comfortable shoes and be aware that there are steep steps involved on two occasions during the walk which expect to have a duration of 90 minutes and will end with a tour of Clifford's Tower to which participants are welcome to stay and ask further questions of Jeremy Ashbee, John Oxley, and Helen Weinstein.

Clifford's Tower learning events, 25th & 27th January 2015: report published online!

Report by Historyworks from the learning events "UNDERSTANDING CLIFFORD'S TOWER AND THE 1190 MASSACRE IN CONTEXTS"

Here is a copy of the Report produced by Historyworks in 2015, free to download as a pdf

We were very pleased to have a full house of 150 attending at both of the learning events about Clifford’s Tower and the wider contexts of York Castle area - organized for the afternoons of Sunday 25th January and Tuesday 27th January 2015. The talks were very informal but informative, and tea breaks gave opportunities to share information about York’s past & present. There are photos of the tours of Clifford's Tower & York Castle area here:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/historyworks/sets/72157650702280165/

We were very grateful for those participants, over 170 who completed our online survey. If you have not already done so, although the 25th & 27th January events are past, we can put you on our mailing list to receive the report about the event and future invitations, so do please please complete the following short survey to describe your reactions and views about historical and contemporary aspects of Clifford's Tower and the Castle area.

2015 HERITAGE SURVEY& EVENTS

If you wish to share your views, then the heritage survey can be found here - and just avoid the first questions about attending events for 2015 now those dates are past, so complete it either in the above box or on SurveyMonkey if you wish to receive the report summarizing the tours and talks about "Understanding Clifford's Tower" or be given invitations to future events about York Castle area.:

https://www.surveymonkey.com/s/YorkCastleJan2015

For 2015 York's Hilton Hotel was chosen for the talks because it is adjacent to Clifford’s Tower and easily accessible, two minutes walk from bus stops on Tower Street, and ten minutes walk from York Railway Station. There is a ‘pay and display’ car park adjacent to Clifford’s Tower and 6 Disabled Parking bays directly opposite the entrance to the Hilton Hotel: 1 Tower Street, York, Y01 9WD. Please see the Google map for exact location.

Tours at 2pm: On both dates the afternoon of tours and talks started with a 2pm walking tour convening at the base of Clifford’s Tower. These tours were customized to the theme for Sunday of appreciating the defensive and symbolic functions of Clifford’s Tower and the context for the Jewish community then and now; and on Tuesday of exploring the long history of death and burial, justice and protest to put understanding 1190 in a much wider context. Both tours involved steep stairs up into Clifford’s Tower. English Heritage kindly opened up the Tower for free to registered participants 2pm to 3pm. However, if the weather is bad we will only stay up in the Tower for a very brief period for those who are particularly interested and then repair to the warmth of the adjacent Hilton Hotel where we have the ‘City of York Suite’ booked for talks to commence at 3pm, many of which will be visually illustrated, but reserved from 2pm onwards if needed to avoid the January cold and bad weather!

“Understanding Clifford’s Tower” on Sunday 25th January 2pm/6pm was organized as an afternoon of tours & talks to explore the site in it’s archaeological and architectural contexts within the York Castle buildings. The talks addressed the significance of Clifford’s Tower to the development of York as a northern power base for Church and Crown from the Norman Conquest onwards, and the meaning for the Jewish communities and heritage communities in York past and present. This event finished in time for participants who wished to walk over to the Clifford’s Tower steps to join the 6.15pm commemorative shared remembrance of the 1190 massacre with a candle-lit ceremony of readings and the Mourners Kaddish (Hebrew prayer) organized by the HMD Committee.

“Understanding the 1190 Pogrom” on Tuesday 27th January 2pm/5pm introduced Clifford Tower’s history of death and burial, justice and protest designed to put the 1190 massacre of the Jewish community in the contexts of wider histories. This event was organized to finish in time for participants to walk over to the Minster for the Commemorative Choral Evensong in the Quire at 5.15pm, to which all are invited, followed by the 6pm ‘Lighting of the 600 Candles’ in the Chapter House to commemorate the 6 million victims who died in the Holocaust.

Speakers: The tours were led collaboratively by Professor Helen Weinstein, Director of Historyworks; John Oxley, City Archaeologist at the City of York Council; and Jeremy Ashbee, Head Historic Properties Curator at English Heritage. The afternoon talks also involved a range of experts from heritage groups and the Jewish community, university archaeology and history departments, and from English Heritage, the City of York Council, York Civic Trust and York Museums Trust.

Commemorating the Dead & Interpreting Traumatic Pasts - 1190 & HMD

PLAQUE COMMEMORATING THE 1190 MASSACRE INSTALLED BY JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY

There is a prominent plaque acknowledging the massacre of Shabbat HaGadol when almost every member of York's Jewish Community perished in 1190. Shabbat haGadol means the Great Sabbath and has particular significance in the Jewish calendar because it is the Shabbat which precedes Passover. The plaque commemorating the tragedy is situated at the base of the Clifford's Tower in York which is a commemorative marker rather than a piece of interpretation. It was installed after a prolonged campaign by the Jewish Historical Society of England.

The plaque text is chisseled in granite and is situated to the left of the staircase up to the Tower: "On the night of Friday 16 March 1190 some 150 Jews and Jewesses of York having sought protection in the Royal Castle on this site from a mob incited by Richard Malebisse and others chose to die at each others hands rather than rencounce their faith HEBREW ISAIAH XLII IV

English Heritage does not mention the 1190 massacre on the website entry for Clifford's Tower. And there is just one interpretation panel of 250 words within summarizing how the Jewish community came to die whilst under royal protection when the Castle was laid under siege and set fire by a mob on 16th March 1190. This lack of interpretation contrasts to the three commemorative markings visible at Clifford's Tower every year.

THE REBUILDING OF A TOWER IN TIMBER FOLLOWED BY STONE STRUCTURE IN THE 13th CENTURY

The paragraphs below will describe the building and rebuilding of the Tower, give an overview of English Heritage's previous interpretation strategy, and describe the three ongoing commemorative markers at Clifford's Tower to the traumatic history of Jewish pogroms. Please note that this is an overview of how it has come to be that the tragedy of 1190 is more commemorated than interpreted around the site at York Castle.

Originally a timber construction built after the Norman Conquest, much of that first building was destroyed in 1069 during a skirmish when the Castle was attacked by Danish invaders. Rebuilt swiflty for defense purposes by the Normans, the timber structure was again destroyed 130 years later in 1190 during riots which led to the massacre of most of York's Jewish population. A timber tower structure was again built for the royal administration in York, but destroyed in a bad storm documented to have occurred in 1228.

The motte has since changed shape, with earth and rubble and concrete and stones added to the base, and what is visible today is the 13th century construction built probably about 15 to 20 foot above the position of the 1190 destroyed timber tower. The stone structure served numerous functions including a treasury for the royal administration, and was extensively renovated and furnished in the 1640s by Henrietta Maria to be used as a royal residence in times of strife during the civil war. The building survived the civil war, but an alleged accidental explosion forty years later in 1684 left only its shell surviving to the present day.

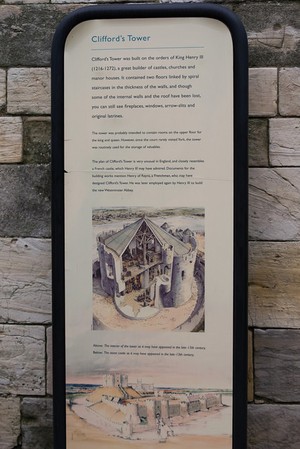

INTERPRETATION STRATEGY OF ENGLISH HERITAGE AT CLIFFORD'S TOWER

Insights about the interpretation strategy of English Heritage were delivered by David Thomas, Interpretation Officer at English Heritage on Monday 28th February 2011 invited by Helen Weinstein to discuss the problems of interpreting and presenting the history of Clifford's Tower in York, and especially the massacre of Jews on the site in 1190. The notes below have been published on this website in 2014 to give an overview of the discussion, to help inform a way forward for a re-presentation of Clifford's Tower.

David Thomas briefly described his own work as an Interpretation Officer for English Heritage, overseeing the presentation and interpretation at over 100 English Heritage sites in his care across the north of England. The sites vary tremendously, from a small section of Hadrian's Wall with a single sign to a large site such as Whitby Abbey, with a visitor centre with multimedia shows and publications. English Heritage's mission is to encourage the public to value the sites, to understand their historic significance, to enjoy them, and to care for them.

The massacre of the Jews in 1190 is, in the language of the English Heritage guidebook for the site, "the most notorious event” related to Clifford’s Tower. How does English Heritage interpret and present such a traumatic history? David first explained how interpretative work is conducted at English Heritage. It is a team delivery, which facilitates a multidisciplinary and collaborative approach, involving curators, conservators, historians, educational specialists, and marketing departments. The work takes into account the uniqueness of each site; each place is looked at in detail and its architecture, heritage, and historical significance are all considered. Fashion in interpretative work changes: for example, the history of women is much more prominent than it used to be, as well as that of the disabled and marginalised groups. Most recently a focused project at English Heritage has been researching properties’ connections with the profits from the enslavement of Africans and investments in the transatlantic slave trade up to the Abolition Act of 1807.

The interpretation team has a crucial focus on its audiences and considers what it is that visitors might want to know. At some sites English Heritage works closely with local communities and stakeholders. The physicality of the sites must also be considered, as this influences what kinds of media can be used. Finally, the marketing is not normally based on a single event or theme, but is designed to make a wide ranging offer for visitors, especially with a focus on the family market. In the case of Clifford’s Tower it is important to English Heritage not to sensationalise the history of the massacre of the Jews. In cases of what may be considered as ‘traumatic history’, such as the York massacre of 1190, care is taken to present more than one viewpoint and thus to include different voices and perspectives. At present, David admitted, this is under developed at the site; however at the same time English Heritage has to acknowledge that Clifford’s Tower has a long history stretching back to the Norman Conquest and therefore it is important to introduce this time depth. The site also receives very high visitor numbers, more than 140,000 per annum, and it is recognised that many of these visitors come for the view of the city from the top of the tower and are therefore not spending a long time on their visit. Any interpretation has to therefore grab their attention and encourage a longer dwell time, whilst also recognising that the site is small and could easily become overcrowded.

INTERPRETATION OF THE 1190 MASSACRE BY ENGLISH HERITAGE AT THE SITE OF CLIFFORD'S TOWER

So how is the 1190 massacre interpreted at Clifford’s Tower today? First of all, said David Thomas, it is not particularly prominent. It is not mentioned at all on the webpage, which mainly presents the physical history of the site and its architecture. At the site of the tower itself, the massacre is described on one of the graphic panels. Text concerning the massacre only takes up six lines on the panel, but since there are only three such panels of approximately 250 words each, this amount may be sufficient if the history of the massacre is not to be overemphasised within the long history of the site. The English Heritage 2010 guidebook to Clifford’s Tower, a forty-page publication, holds a two-page description of the massacre and an additional page explaining the background.

This is much more than was offered by English Heritage in the past. The 1987 guidebook held very little detail of the massacre and only dedicated six lines to describing it. The 1997 guidebook had two pages on the history of the Jews of medieval York more generally, describing the massacre in 1190 along with other things. In comparison, the already mentioned 2010 guidebook has two pages focusing on the events in 1190 alone, so clearly there is an increasing focus on the history of the massacre. In the future English Heritage may want to do more, possibly with guided tours. But, David stated that ‘first-person’ tours, re-enactment-style events or ghost tours concerning the events of 1190 are not likely to take place, as it is necessary to respect the sensitivity of the subject and the site.

COMMEMORATIVE PLAQUE & ACTIVITIES OF JEWISH GROUPS IN UK AND USA

Interestingly, it seems that the history of the massacre is actually more commemorated than interpreted. Most obviously there is the plaque at the foot of the steps leading up the Tower, which was installed after a prolonged campaign by the Jewish Historical Society. Before 1978 the Ministry of Works, the forerunner of English Heritage, who administered the site, did not allow commemorative signage. English Heritage, in contrast, has been open to commemorative activities by the Jewish community locally, nationally and internationally. The plaque laid by the Jewish Historical Society was part of an act of reconciliation between communities and was part of a ceremony led by the Chief Rabbi and the Archbishop of York.

COMMEMORATIVE DAFFODILS REPRESENTING STAR OF DAVID TO BLOOM ON 16TH MARCH

The commemorative marking that is most visible to residents and visitors is the striking special daffodils that bloom over the mound in March every year to mark the massacre. This planting came about as a result of a three-day commemorative event in 1990, and in the early 1990s, in a co-operative venture between English Heritage and the American Jewish Foundation, six-leafed daffodils were planted all over the grassy mound surrounding Clifford’s Tower.

This type of flower was selected to signal a connection to the Star of David, and because they bloom early, in mid-March, near the date of the massacre, which was on the 16th of March 1190. However, because the commemorative daffodil significance is not acknowledged or publicised at the site or online at English Heritage, this symbolism is not widely known.

ENGLISH HERITAGE WEBSITE FEATURES THE DAFFODILS BUT AVOIDS THE JEWISH TRAGEDY

Indeed, the English Heritage webpage for Clifford's Tower prominently shows the mound with the flowering daffodils, but the text refers to the site in the context of royal power and as a scenic tourist attraction for viewing York today:

http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/cliffords-tower-york/

"The stunning panoramic views from the top of Clifford’s Tower, out over the historic city of York, makes it one of the most popular attractions in Yorkshire. Set on a tall mound in the heart of Old York, this imposing tower is almost all that remains of York Castle, which was originally built by William the Conqueror. There’s plenty to discover here. In its time, the tower has served as a prison and a royal mint, as well as the place where Henry VIII had the bodies of his enemies put on public display."

INTERPRETATION & MARKETING OF CLIFFORD'S TOWER BY ENGLISH HERITAGE

Thus, there remains, perhaps, an unresolved tension between the interpretation and marketing of Clifford’s Tower, which broadly focuses on medieval architecture and royal power and life in the castle, and the interpretation and presentation of the massacre in 1190. The latter is still not very visible at the monument, and although English Heritage has supported the annual commemorative event and Kaddish for the dead recited by a member of the Jewish community to mark Holocaust Memorial Day organised by York City Council at the base of Clifford’s Tower, perhaps English Heritage as a heritage organisation needs to take responsibility for communicating 1190 more comprehensively: the narrative, its meaning, and its commemoration.

Holocaust Memorial Day 2015: Tuesday 27th January

Each Year on 27 January on Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD) people across the world remember all those whose lives were destroyed in the Holocaust and the countless lives lost through other genocides and persecutions around the world.

The programme of events are held on and around the 27th January to commemorate the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and death camp in January 1945. HMD has been held in the UK since 2001 and the City of York has been marking this occasion since 2008.

On the invitation of York City Council there has been a marking of 1190 as part of the Holocaust Memorial Day programme by requesting Helen Weinstein to lead a Jewish History trail ending at the site of the massacre at Clifford's Tower. It is perhaps fitting to mark HMD at Clifford's Tower because it is the site of a traumatic past where a community was massacred because of their ethnicity.

English Heritage has kindly opened Clifford's Tower for Helen Weinstein to discuss the Jewish history of York with interested members of the public as part of the civic programme as an act of engaging with and understanding the past. Many hundreds have attended these discussions, mostly residents of the city, wanting to know more about their Jewish neighbours past and present. However it has always helped that elders of the Jewish community from York, Leeds, Knaresborough, Selby, Halifax, Scarborough and Middlesborough have attended the Jewish History trail too, to discuss the lives of Jews in Yorkshire from the Norman times to the present day.

Also, the committee for HMD in York always ensure that it is not only Jewish pogroms that are remembered. On HMD 2015 it will be 70 years since the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. 2015 will also be the 20th anniversary of the Genocide in Srebrenica, Bosnia. Therefore it is particularly appropriate that the theme for this major anniversary year focuses on memory. All those persecuted around the world will be remembered. See more at: http://hmd.org.uk/resources/theme-papers/hmd-2015-keep-memory-alive#sthash.tuUzLGsV.dpuf.

York’s HMD programme enables those living, working and visiting the city to come together to reflect individually and collectively, to learn the lessons of the past and seek to create a safer, better future. It is believed that in remembering and acknowledging the past we can each help to promote a more tolerant and inclusive society for the future.

Recommended Reading on traumatic pasts:

- LaCapra, D. 2004 History in Transit: Experience, Identity, Critical Theory (Ithaca), 106-144

- Logan, W. & K. Reeves (eds.) 2009 Places of pain and shame: dealing with 'difficult heritage' (London)

- Pickering, P. & Tyrell, A. (eds.) 2004 Contested Sites: Commemoration, Memorial and Popular Politics in Nineteenth Century Britain (Aldershot)

Interpretation - Clifford's Tower - English Heritage

Clifford’s Tower is maintained and run as a publicly accessible site by English Heritage. To find out about opening times, location, and visitor access, please visit their website: http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/cliffords-tower-york/

You can see a selection of photographs taken by the Historyworks team showing views of the precinct and the interpretation on site at Clifford's Tower courtesy of English Heritage. Also fantastic drawings from the York Art Gallery collection depicting Clifford's Tower courtesy of York Museums Trust:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/historyworks/sets/72157649049500342/

The following text is an overview by Historyworks of English Heritage’s interpretation and use of the Clifford's Tower.

The 1190 Massacre of Jewish citizens

At the base of the mound on which Clifford’s Tower is situated there is a plaque which commemorates the massacre of York’s Jewish citizens in 1190 which was installed by the Jewish Historical Society of England.

The commemorative plaque, inaugurated with a service of reconciliation in 1978, provides historical information about the massacre and commemorative events take place at this site each year, organized as a civic occasion by York City Council on HMD, Holocaust Memorial Day, marked in the UK on 27th January. See next section on "Commemorating 1190 & HMD" for further details.

Ground Level

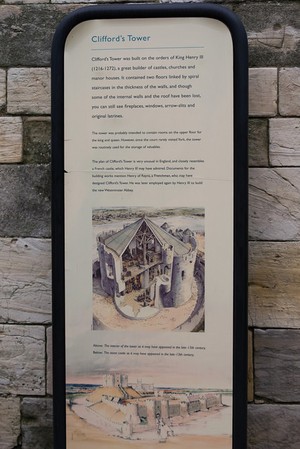

Once you have walked up the steps and entered the tower it is likely that the site may feel smaller than you first expected. English Heritage utilise the space by employing four methods of interpretation on site - information boards, a miniature scale model, an official guidebook, and a visitor’s centre/shop.

The ground level contains a visitor shop that sells historically-themed merchandise ranging from toys and stationary to sweets, replication armour, and books. The merchandise is largely medieval-based, with less attention shown to the site’s more modern histories.

This emphasis on the medieval is balanced through the use of vertical information panels that are unobtrusive yet accessibly positioned. The illustrated panels chart the history of the Tower from its construction in the Norman period, the massacre of the Jewish community in York in 1190 in a timber Tower no longer visible on the Castle mound, the reconstruction of a stone Tower in the 13th century and its decline in the 16th and 17th centuries to its current ownership by English Heritage. These are very much focussed on the Tower’s changing structural features over a linear chronology.

The ground level also has a miniature scale model of the tower and castle complex that provides a tactile and helpful visualisation of the structure and the castle complex during the Middle Ages. Around the base of the model are four information panels that give the visitor information about how the castle complex was used. These explore how the castle was built, what it was used for, and who used it. These panels are also written in braille.

First Level

A small room is still intact and accessible on the first floor, labelled as the chapel in the guidebook. This room has very little in signage or interpretation except for a large storybook on an easel. The pages in this have text and images aimed at younger visitors and is similar in style and content to their ‘Step Inside Activity Pack’ which can be viewed and downloaded here: http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/publications/step-inside-cliffords-tower/cliffordstower.pdf.

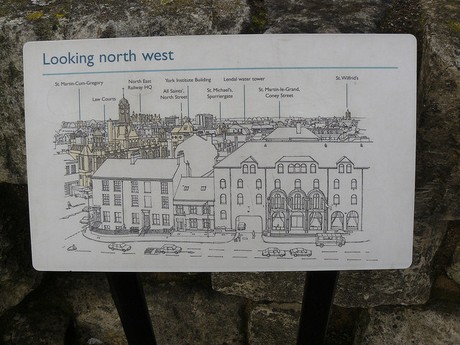

Wall Walk

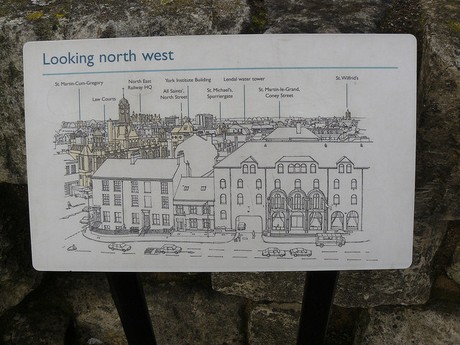

On the highest level of Clifford’s Tower the visualisation of York's architecture is presented on information panels. There is very little interpretation available on these. Instead, line drawings of the skyline that is visible from various points around the upper wall are shown, with key buildings from York’s contemporary skyline highlighted to assist the visitor in identifying them.

This is aligned with English Heritage’s marketing of the tower which states on their website: “The stunning panoramic views from the top of Clifford’s Tower, out over the historic city of York, makes it one of the most popular attractions in Yorkshire.”

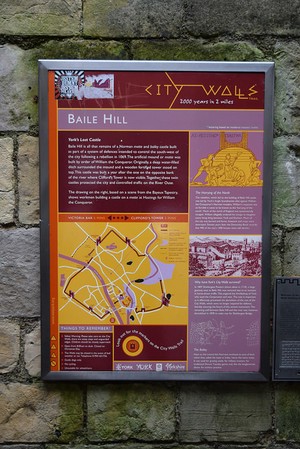

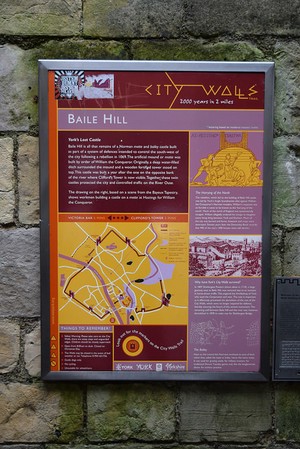

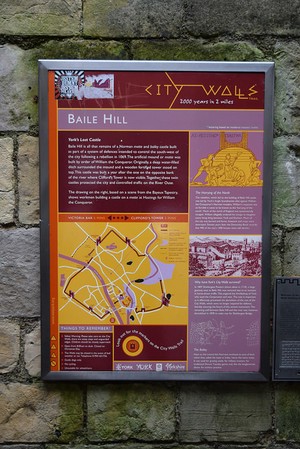

Baile Hill

Situated over the river is a corresponding motte to the one at Clifford's Tower, which is called Baile Hill, the remains of a second Norman motte and bailey castle, constructed following orders by William the Conqueror in 1069. The interpretation of the location primarily centres on this aspect of its history through the use of a wall mounted display that makes up part of the City Walls Trail.

A description of its origin, its physical appearance, and its role in York is supported by an illustrated text that provideS wider contextual information about why it was built and how the city walls have survived, offering a link between its early and more recent history.

Overview

English Heritage covers a large amount of the site’s history concisely. All the information is given through text, pictures, and in one instance a model and a digital information pack to be accessed off-site. Although the structure and restricted space make displays problematic, digital technologies may provide an answer to providing more nuanced information and varied interpretation possible.

Online

English Heritage has a fifth vehicle of interpretation offsite via the online website. However, this has little information for the user to understand the long duree of the castle complex, beyond a focus on the medieval heritage and architectural interpretation:

http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/cliffords-tower-york/

Interpretation – City of York Council

The City of York Council provides very little on-site interpretation of the Castle complex generally or Clifford's Tower more specifically, despite the fact that the City Council is the major landowner in the Castle/Piccadilly area, owning the land surrounding the tower and motte consisting of park, pavements, roads, and a substantial car park. The Council does, however, provide resources online but these are grouped under sections focused on York's city walls.

The digital interpretation is contained on webpages that offer historical overviews of York Castle, Clifford’s Tower, and The Old Baille. A History of the City Walls and is also available to download online as a PDF.

The content on these webpages are short, concise, and provide an easy-to-understand historical description of the main changes and events that occurred at each of the sites.

The only physical on-site interpretation for York Castle complex exists at Baile Hill (a corresponding motte located over the river) in the form of a wall-mounted display. This is part of the City Walls Trail and there are corresponding interpretation panels at Bootham Bar and Walmgate Bar and the Multangular Tower, and this interpretation scheme continues the association with York's city walls that exists online.

There are no information panels or other signage provided by the City Council closeby Clifford’s Tower and the older castle complex that would indicate to visitors or residents that the site is of historical significance.

Redevelopment Discussions

In recent years, discussions within the City of York Council and the public have explored the understanding and interpretation of the York Castle site, and the possibility of improving the area through redevelopment. This would encompass the area occupied by the car-park, Clifford’s Tower, the Eye-of-York, Tower Street, and the River Foss.

In 2008 a planning document entitled "The Castle Piccadilly Development Brief of 2008" established an assessment as to how the area could be physically developed without compromising Clifford Tower’s dominance and centrality. City Council development updates on the Castle area:

http://www.york.gov.uk/info/200382/major_developments/377/major_developments/2

The plan also focused on establishing the space as a public and civic space, remaining faithful to the current open-air nature of the site and its historic traditions.

Discussions and workshops with the public showed that participants felt the hidden stories and archaeology of the area was the “missing ingredient that unified and made sense of the area. “ The participants also articulated a sense of disconnectedness and indifference to the area, centering on the car park and roads as a factor in that emotional and physical distancing. It was felt that the histories of power and justice that dictated the historical development of this area has been lost and are not made available to visitors.

There were anxieties about redevelopment schemes and the inclusion of private developers. The public consultations found that people preferred the prospect of bringing together partners from the City of York Council, York Museums Trust, and English Heritage to co-ordinate management of the area in ways that extract the potential of the site as a place of local, national, and international significance.

Interpretation - York Castle Museum's Prison Exhibition

York Castle Museum is run by York Museums Trust. To find out about opening times, the location at the Eye of York, and the current exhibitions, do please visit their website: www.yorkcastlemuseum.org.uk

You can view a selection of photographs taken by the Historyworks team on site at the York Castle Museum of the interpretation courtesy of York Museums Trust:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/historyworks/sets/72157648874827449/

The following text is an overview of York Castle Museum’s interpretation and use of the Debtor’s Prison and Female Prison. Some of the titles refer to the museum’s own exhibition titles.

What is your connection to the York Castle?

This section, immediately accessible upon entering the part of the museum that is dedicated to its history as a prison, engages with the visitors’ own familial history.

The museum taps into the growing interest in family history and helps facilitate individual research within the museum’s database, creating links between visitor, collection, and site. This is delivered in an accessible way through the use of two interactive screens situated in an open cell accompanied by a large metal bed, wooden wash basin, and cabinet holding a firearm that is contextualised with an explanatory text.

The database of prisoners is also available online, opening up the castle’s records to a wider audience and enriching family history research: http://www.yorkcastleprison.org.uk/family-history.html

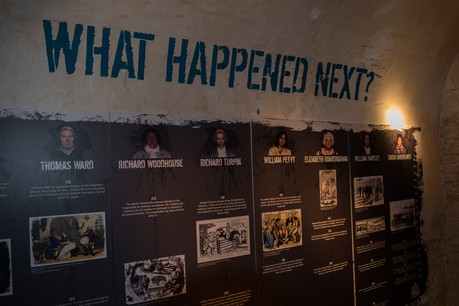

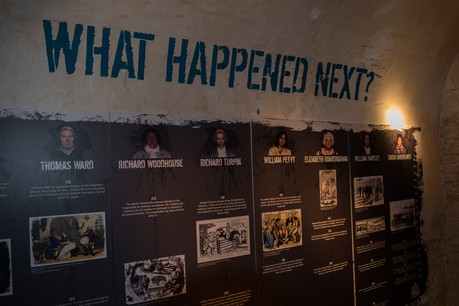

What Happened Next?

This section of the exhibition uses a corridor space to present a text-based interpretation of the site. It achieves this through the use of a pull-up banner containing historical context with concise information about the history of the prison.

Alongside this is a mural that presents a timeline of significant national and local prison history, concisely contextualising individual case studies of imprisoned men and women (including the popular figure Dick Turpin) alongside wider developments such as the abolition of the death penalty.

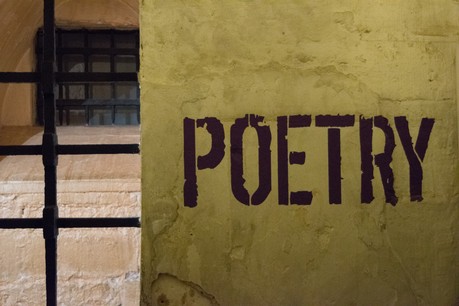

Poetry

One of the cells in the prison is dedicated to poetry. This cell, empty except for walls illustrated with inmate’s mugshots, uses the inmate’s creative responses to their time in gaol to provide an insight into the history of the building. This offers an interesting angle on interpreting the space and history of the building. Upon entering the cell, a sensor triggers a reading of poetry. This is a particularly engaging illustration of prisoner’s experience that helps connect the museum visitor with the room in which they’re standing.

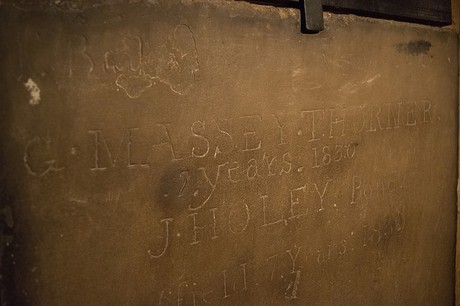

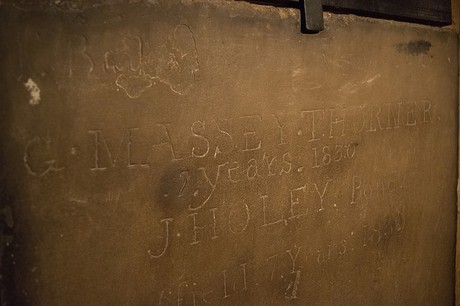

Prisoner’s Graffiti

Prisoner’s graffiti is visible throughout the Debtor’s Prison although it is not always highlighted. There are examples of prisoner’s scratching their own names, depictions of Christ and gaolers, as well as a prison maps that have been etched into the cell walls.

Examples of museum-presented graffiti are the flagstones that once lay outside in the exercise yard and now hang on the wall in the Debtor’s Prison. The exhibition of the flagstones continue the museum’s focus on prisoner experience through the highlighting of the literal marks they make on the spaces that they were inhabited.

A Thousand Years of Justice

This room is dedicated to the wider history of the prison system within the castle complex and provides a mix of artefacts, wall displays, and digital projection to present a history that spans nearly 1,000 years.

It delivers concise historical information across each of the formats. The wall murals show pictures and artist’s representations of the castle complex from creation through to the 1930s, accompanied by succinct text. Artefacts of incarceration are displayed in a cabinet whilst a projection onto the floor charts the history.

The Petitions

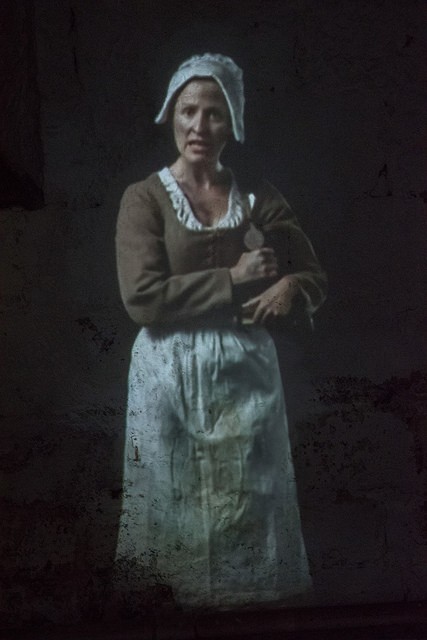

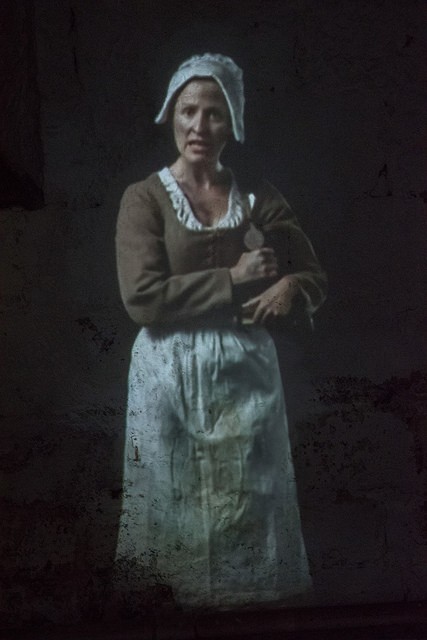

This cell uses digital projection to tell narratives about prison corruption and the prisoner’s dissatisfaction with the behaviour of the gaolers. A seated area provides an opportunity to rest and watch an actor projected onto the wall read the prisoners’ petitions.

Four text displays outline the petitions enabling visitors with hearing difficulty the opportunity to read the case studies shown in the projection.

Interestingly, the room also contains its original door, now cased in glass.

Cells and use of projection/audio storytelling and soundscapes

A larger section of the Debtor’s Prison is used to tell the stories of individual inmates. These are delivered in a space-conserving manner through the continued use of projection. Each individual cell contains a projection of an actor delivering a narrative from the viewpoint of an inmate, and in one instance a prison guard. The range of experiences that they explore (male, female, child, adult, inmate, and gaoler) is both engaging and illustrative of the history.

One cell in particular provides a visceral response that communicates the prisoner experience very well and as a result speaks about the wider conditions and behaviour of the York Castle prison. This is a cell that is pitch black and upon entering the sound of men struggling for breath can be heard before text is shone onto the wall providing context for the unsettling sound.

Women’s Prison and the Condemned Cell

The area of the museum that was once the women’s prison has undergone significant changes since it’s time as a gaol, with many of the features that mark it as a prison now masked and reinterpreted for visitors, rather well, as a Victorian street.

This area of the museum yields little in terms of interpretation about its time as a women’s prison and the cell that interned condemned individuals awaiting execution is currently fashioned as a Victorian undertaker’s workshop. This may seem appropriate but there are no direct interpretative links made to its previous function or the inmates that were held there, unlike the Debtor’s Prison.

Overview

The museum focusses on the lived experience of prison life with wider contextual information used to frame personal accounts and individual responses to the site. The displays aren’t intrusive or dominant within the spaces and therefore allow visitors to engage with the architecture of the prison without compromising the information they want to deliver and the stories they want to tell.

Overview of York Castle History

UNDERSTANDING CLIFFORD'S TOWER HISTORY & THE YORK CASTLE PRECINCT

Clifford’s Tower has had a turbulent history. The structure has been modified or rebuilt on many occasions. The tower as a timber building was destroyed by fire under attack by Danish invaders in 1069 and again when besieged and burnt to the ground in 1190 when the Jewish community were massacred. It was damaged during bad storms in 1228 when the timbers again collapsed, after which the Tower was built more solidly as a stone structure that we see as a ruin today. Built intermittently between 1245 and 1290, the Castle was probably most complete in the early 1300s, but by the late 1500s it was semi-dismantled when stones were removed and sold by an unscrupulous officer, with complaints recorded in 1596 about the gaoler selling off substantial quantities of stone. In the early 1640s it was renovated with a new roof and floors to accomodate royals and a garrison during the Civil War. However, a few years later fire struck again in 1684, burning the inner timber structures, most likely including a Chapel built by Henrietta Maria in 1643. It is therefore a complex site in terms of the architectural history.

The mound & tower is also unique historically because this Castle fortification was used by the Crown to govern the north. Clifford’s Tower was at the heart of this Castle precinct and has been a site of violence and death over many centuries. Not many know that it was used for political repression after the medieval period, for example, when Robert Aske was hung from a cage to die a painful traitor’s death in 1537 for his role in the revolt called 'The Pilgrimage of Grace'. It was also a place of incarceration of Quakers including George Foxe in 1665, punished for speaking out at York Minster. Notoriously, it was the site where Peterloo protesters were incarcerated after the massacre at St George's Fields in Manchester in 1816, and before that 17 Luddite activists were brought to be executed in 1813.

The larger prison complex surrounding Clifford’s Tower was not dismantled until 1935 when rubble was probably dumped onto the mound, and it is this long history of death and violence, building and rebuilding that will be outlined in the sections below.

Historyworks is collecting drawings and photographs showing Clifford's Tower in the past and present. There is a group of photos on the "Imagine York" site which interestingly show the mound with a different shape and the defensive wall:

IMAGES ON HISTORYWORKS FLICKR SITE

We have also gathered together images (including some fantastic prints and drawings) from the new Historypin project at York Museums Trust, and you can see these alongside other photographs takent by Historyworks whilst leading history trails here:

Early History - Roman Burial Site

There is significant evidence of Roman burials from archaeological excavations - skeletons, sarcophogi, burial objects - showing that the Castle area was previously the site of a Roman Cemetry. Burial was not permitted within areas occupied by the living, and the location at the Castle yard is consistent with this, positioned on a major route closeby but outside the Roman habitations in York. To find out more about Roman York, go to the Historyworks trail (audio & script & map) called "Walking with the Romans: Daily Life in Eboracum"

Prior to the Roman settlement in York, it is possible that there was also a mound or site of significance for the Celts on the Medieval tower site, but there is no firm evidence at this stage. There is no domestic or military finds for Roman occupation of the Medieval castle mound site, excepting the important burial finds,which show this was a place for the dead rather than the living. The skeletons include men, women, and children.

The inscriptions on burials found in the Castle Yard area have led to the suggestion that this might have been the location of a burial club of the centurionate. For example, a stone coffin found earlier than the 1956 works, was a stone coffin with the name AURELIUS SUPER, a centurion of the VIth Legion.

What is known from findings in the 20th century, which do not allow us to understand the entire area but only the places where drains were installed in 1956 (between the steps to Clifford's Tower across to the door of the Female Prison, now the side wing of the York Castle Museum), is that this portion of the Castle precinct was used for burials.

Interestingly, a range of burial types were identified, showing that the cemetry was used by Romans over time, with some burials of high status shown by the type of stone coffins and burial goods. One of the stone coffins, discovered in 1956, had the name JULIA VICTORIANA inscribed, showing that it was made for the wife of a centurion of the VIth Legion. Fragments of wall plaster and building stones suggested a high status burial of coffins within a tomb surrounding. A skeleton of a young woman, found nearby, had associated finds of grave burial goods, including three bronze and two bone bracelets which were attached to her body by a leather thong. A Castor ware beaker was found beneath the body, and closeby pottery sherds and a small perfume flask.

These finds are intriguing, and it would be useful to revisit the archaeological evidence. Further, if the opportunity arose for a larger area to be investigated between the Tower's steps and the Castle Museum's Female Prison Building and Debtors' Prison, across the Eye of York, it might be possible to learn more about Roman burial practices in York, and more precisely to establish the size and scale of the Roman cemetry.

Information on stone coffins in Roman era: John Oxley, City Archaeologist, City Council, York

Information on Castle Yard: H.G. Ramm, "Roman Burials from Castle Yard, York" in York Archaeological Journal, 39 (1956-58), pp 400-418

Norman Castle - Attack by Danish Invaders

Shortly after the Norman Conquest in 1066 there were revolts across the North of England. As William the Conqueror and his army progressed northwards they built castles at strategic places across the country, establishing one in York. This castle is the early incarnation of what we recognise as Clifford’s Tower.

The castle was constructed out of timber and built on an artificial mound, also known as a motte, and surrounded by an artificial ditch, known as a bailey. William left the structure guarded by a garrison of 500 men as he returned South, satisfied that the rebellion would be beaten.

However, William was forced to return to York in 1069 when a force of Northumbrians, fighting under Edgar Ætheling, attacked the city as part of a greater revolt known as the Harrying of the North. The revolt was swiftly defeated as the besiegers were either killed or forced to flee.

A second assault on the castle was made as a large Danish fleet, called on for support by Ætheling, sailed up the Humber to meet with the Northumbrians and mobilised on York. In defence, the York garrison began to burn the surrounding houses in an attempt to prevent the attacking forces using the wood to bridge the ditches to the castle. The Danes also set the city on fire and the castle was eventually overcome and destroyed.

This prompted William to return once again and destroy the land around the surrounding countryside, pressuring the Danes to retreat back down the Humber. William spent the winter of 1069 in York whist his forces continued to destroy livestock, crops, farms in the surrounding area. The castle was rebuilt in 1070 but the damage done to the region was so great that it resulted in famine and in teh Domesday Book, written in 1086, most of the region was described as "waste".

There was relative stability and peace at the castle for the next century until a rebellion against Henry II in 1170 resulted in adaptations being made. In 1973 a gaol was added and money spent on the tower, the predecessor to Clifford’s Tower.

Overview: The Jewish Community of York

Jewish people first came to Britain in significant numbers from Normandy after 1066 and the invasion of William the Conqueror. A century after their arrival to fund and support the Crown's fiscal administration and power base in the north, the history of York's Jewish community was marred by massacre in 1190 when nearly all the families died in the Royal Castle Keep, most likely a timber structure, where presently there is a stone keep known as Clifford's Tower. The massacre of the Jewish community in York was related to anti-semitic attacks in London, Lincoln, Norwich following the coronation of Richard I, when there were arson attacks against many Jewish homes and Jews were killed in numbers. In York, it was estimated by chroniclers that 150 members of the Jewish community died when the keep was set fire and families there who had gone to the Castle as a place of Royal protection were killed.

However, a few members of the Jewish community survived, and with new arrivals from Europe, the population recovered, even in York, with some significant dwellings and a synagogue located on Coney Street, just five minutes walk from the Castle. Thus, by the middle of the 13th century many Jewish people had homes in the city, including Aaron of York, holding the position of Archpresbyter, the leader of the English Jewish community from 1236 to 1243. York continued therefore to be at the core of Jewish life in York up to the expulsion of Jews from England in 1290.

Jews did not come back to England until they were invited in 1656 by Cromwell, but it is unlikely that any Jews came to live in York until the late 19th century, and we have evidence of a small community of Jews working at an improvised synagogue for several generations above the Bowman family Joiners' shop on Aldwark. The younger generation of Jews in York today are mostly affiliated to the University, as students and researchers, administrators and manager. On the last census there were just over one thousand Jews counted in the census of 2001 but numbers are growing as the city and university develop, and there is even a Jewish community group meeting regularly on Friargate at the Quaker Centre, just steps away from the place of the massacre in 1190.

What is for sure, is that there are no generational blood links connecting the Jewish community in York today to the families who were massacred in 1190 in York Castle. However, there are commemorations at the site of Clifford's Tower, inaugurated with the plaque and service of reconciliation in 1978.

There is a leaflet and audio tour linked below on youtube, started as a research project organised by Helen Weinstein as Founding Director of IPUP, working in partnership with the City Archaeologist, John Oxley. The project was assisted by IPUP Interns who are postgraduate students from the University of York: Jon Cook, Hannah Lyons, Daphne Mayer, Alex O'Donnell, Tom Sutton, Bill White, and Ben Wilkinson. You can access the early version of the project by youtube and by using the associated scripts, whose content was shaped by Helen Weinstein and John Oxley.

However, since then, the project has developed, and with the support of John Oxley at the City Council and Michael Woodward at York Museums Trust, it has been updated by Historyworks to be more suitable as a product for a mass audience, and delivered as an app. You can listen to the updated trail by clicking on the sections on audioboo, downloading the shorter scripts. The production by Historyworks was recorded by Jon Calver, narrated by Jonathan Cowap of BBC York, with the script updated by Helen Weinstein, edited by Sam Johnson, supported by script advisor John Oxley.

The Massacre of 1190

In the hours before and during 16th March 1190 nearly all of the Jewish population in York perished on the site of the Castle keep, a timber structure destroyed during the attack, probably about 15 to 20 foot below where the present stone structure of Clifford's Tower stands today atop the motte.

The massacre of the Jewish community, about 150 men, women, and children, is probably the most well known part of the history of York's Medieval Jewry. However, the York Massacre was in fact only one of a series of attack on communities of Jews across England.

The Crusader King - Coronation & Anti-Jewish Riots

The events of 1190 really began the previous year, at the accession of Richard I. Following the death of his father Henry II in July, Richard's Coronation was held on September 3rd, 1189. An anti- Jewish riot broke out after a delegation of Jews who had travelled to London for the occasion attempted to enter the Palace of Westminster during the coronation banquet.

Around 30 of the Jewish delegation died in the riots that followed the Coronation. Amongst those seriously injured was a wealthy moneylender from York called Benedict. The tension around the Coronation and the murder of Jews on the streets of London is put into a wider context of similar pogroms against Jews in Europe by Simon Schama (see Reading List below).

Despite the King's order that the Jewish community be left in peace, a series of further anti-Jewish riots spread across England in the Spring of 1190 following Richard I's departure from England on Crusade. Christian prejudice against the Jewish community living amongst them had certainly been heightened by the Crusader preaching and whipped up in recent years by accusations of ritual child-murder. See the helpful explanation of this traumatic allegation researched and written by Simon Schama (see Reading List below).

Although genuine bigotry was certainly one of the reasons behind attacks on the Jewish community, so too was the Jews' legal and economic position. As major creditors of royal government, the Jews were granted legal exemptions and special royal protection. Wealthy, but vulnerable, the Jews of England were easy targets for local interests chafing against increasing royal control.

In March, the violence of anti-Jewish rioting spread to York, where royal control had recently been weakened following the replacement of the region's powerful sheriff. A group of men had attacked the house of Benedict of York, killed those within, and set fire to the building. Therefore, because the Jews were under Crown guarantees, most of the Jewish community of York took refuge in the Keep of the Royal Castle (a wooden building on the motte, probably about 15/20 foot below where the stone structure of Clifford's Tower was built and rebuilt between the 1200s and 1600s), where the Jews would have expected Royal protection by the King's agents.

More violence followed, and it seems that the key agent of the crown was abroad at the time, and this meant that protection from the constable or sheriff in York was delayed and a series of errors of judgement ensued. An order was given that the Jews be ejected from the Keep by force. Although it was quickly rescinded, this order served to incite the mob who began to lay siege to the Castle.

By the evening of Passover on March the 16th, as siege engines stood closeby the York Castle walls, the Keep where the Jews were sheltering was set alight and most of the Jewish community died within the Keep or closeby. With royal agents absent at the crucial time of tension, local men of stature did not intervene to save the Jewish community, instead they showed their interest by going to the Minster where the documents of the funds owed to the Jews were kept, and had these burnt.

1190 - Contested Narratives

How the medieval Jews died is a matter of sensitivity in the Jewish community of York today, because the medieval accounts of the time were most often written with an anti-semitic agenda, and claiming that the Jewish men slayed their own families in a mass act of suicide was possibly a way of the chroniclers deflecting blame from their own Christian community. However, whether by suicide or at the hands of others, it is indeed difficult to navigate the narrative accounts written for rhetorical affect, many of these accounts being written at a distance of time and place. But what is for sure was the fate of the Jewish community, because die they did whether murdered by fire, hand, implement.

A new book of essays edited by Sarah Rees Jones & Sethina Watson (see below) considers the massacre as central to the narrative of English and Jewish history, exploring how a narrative of events about 1190 was built up, both at the time and in following years.

1190 to 1290: The Fate of the Jewish Community in York

Remarkably, within decades of the massacre, Jews were resettled in York, and seem to have been for a short period in the 1220s to 1240s to have been more prosperous, numerous, successful as before the gruesome event of the 1190 massacre.

King Edward's policy towards the Jews in England blew hot and cold throughout the period, with restrictive legislation and punitive fines, the community had already declined in the years leading up to the 1290 expulsion.

Therefore by 1290 when Edward I formally and finally expelled all Jews from his kingdom, a severe decline had set in. At his accession in 1272, the population has been reckoned again to have numbered about 150 persons.

Web Links & Further Reading

-

Readers with a general interest in the history of England's Jews should begin with the excellent bibliography prepared by the Jewish Historical Society of England.

- Robin R. Mundilll, The King's Jews. Money, Massacre, and Exodus in Medieval England, (Bloomsbury, 7 June 2010) is an excellent synthesis of research on the history of medieval Jews of England weaving manuscript and secondary sources to present a very readable overivew for the general reader of how Jews lived and worked alongside their Medieval Christian neighbours.

-

Most recent set of scholarly essays has been published by Boydell & Brewer edited by Sarah Rees Jones & Sethina Watson, Christians & Jews in Angevin England (19 April 2013)

-

P. M. Tillott (ed), A History of the County of York: The City of York (1961) pp. 47-49.Available online to subscribers and members of subscribed institutions at the IHR's British History Online Pages

- Simon Schama, The Story of the Jews. Finding the Words 1000BCE-1492CE (Bodley Head, 2013) pp 292-326, provides a useful context of the hostile enviornment for Jews in Europe and the pogroms flaring up across European centres where Jews were living and working in the years prior to the 1190 pogrom in York and elsewhere in the UK.

-

R. B Dobson, "The Jews of Medieval York and the Massacre of March 1190", Borthwick papers 45 (York: St. Anthony's Press, 1974, revised ed. 1996).

- R. B Dobson, "The Decline and Expulsion of the Medieval Jews in York,"Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society 26 (1979): pp. 34-52.

On traumatic pasts:

- LaCapra, D. 2004 History in Transit: Experience, Identity, Critical Theory (Ithaca), 106-144

- Logan, W. & K. Reeves (eds.) 2009 Places of pain and shame: dealing with 'difficult heritage' (London)

- Pickering, P. & Tyrell, A. (eds.) 2004 Contested Sites: Commemoration, Memorial and Popular Politics in Nineteenth Century Britain (Aldershot)

Audioboo & Scripts: York Jewish History Trail by Historyworks

In 2014, the York Jewish History Trail was revised by Historyworks following new research. This involved the updating of the script by the Historyworks team, Helen Weinstein and Sam Johnson, along with a new recording of the audio by Jon Calver. The updated script was narrated by Jonathan Cowap of BBC Radio York, with support from script advisor John Oxley. Please credit the team that devised the Jewish History Trail, in particular Helen Weinstein (Director of Historyworks) & John Oxley, (the City Archaeologist, York City Council) if you wish to publish the script, app, map, audio, photography for circulation & sharing on websites and social media.

The Medieval Castle

The tower we recognize today was built in the second half of the 13th century, following the destruction of the castle during the massacre in 1190, and a further collapse of a wooden tower in 1228. In 1237 a house was built in front of the gaol for King Henry III to reside in. Under orders from the king in 1245 a rebuilding of the tower in stone began. However, this was a slow and stalled process as it took 17 years until the castle reached near completion in 1262.

York’s significance in the north of England meant that the newly strengthened castle was not used as a royal residence but as a stronghold, reinforcing the fortification of the city. This is evident as the castle complex comprised of a gaol, a mint, and law-courts, in which functions of central government, including the Exchequer, were temporarily housed in the castle during periods of intense Anglo-Scottish warfare.

The law-courts and the prison remained at the castle until the 20th century, and the Magistrate Court is still on-site.

Naming Clifford's Tower

The rebuilt tower, combined with the castle complex in York, symbolised royal power and authority and its function as a gaol may have led to the naming of the tower.

The first instance of ‘Clifford’s Tower’ being used can be found in documents detailing a scandal involving the castle gaoler, a Robert Redhead. Redhead was accused of attempting to demolish derelict parts of the tower in 1596 and sell the stone for lime-burning.

Despite the mention of the name in 1596, the name is believed to originate from much earlier. The castle is believed to have a rather unfortunate namesake: the rebel baron Roger de Clifford. Clifford, forced to surrender at the battle of Boroughbridge in March 1322, was held captive in York, hanged, and his corpse displayed and hung in chains on a gibbet at the castle.

In the autumn of 1536 the Pilgrimage of Grace uprising took place. The protesters, revolting against Henry VIII’s fracture with the Catholic Church and dissolution of the monasteries, were led by the infamous Robert Aske. Aske was a barrister from a Yorkshire family who soon rose to the forefront of the uprising.

At it's strongest, the resistance was comprised of approximately 40,000 armed rebels. Following a number of successful campaigns, Aske sought to negotiate and reason with the King, discussing the motivations of the protesters. The King granted Aske safe passage as long as the rebels were stood down, but as he returned to Yorkshire violence broke out again and the King ordered the seizure and imprisonment of Aske in the Tower of London.

In the following weeks, 216 of the rebel leaders were rounded up and executed. In keeping with the Castle’s history as a site for displays of monarchal power, Aske was tried and convicted of High Treason, brought to York, and on the 12th July 1537 he was hanged in chains, and displayed “from the height of the Castle Dungeon” as a warning to other would-be rebels.

Robert Redhead - The Dismantling Gaoler

By 1596 the tower was unused and growing increasingly dilapidated. The poor state of the tower was partly due to the tower's gaoler, Robert Redhead.

Redhead had been steadily dismantling sections of the uppermost part of the tower and flanking wall to assist in the construction of a cockpit for the sport of cock-fighting. This behaviour outraged the locals and a petition forced Robert to stop.

However, later that year rumours began to spread about Robert and a group of accomplices who, under the guise of using the stone for repairs to other sections of the complex, were selling the stone for lime-burning.

In 1597, Redhead and his men were caught throwing stone from the top of the tower and rollign them down the mound. Other accusations suggested that Redhead was also using rabbits to undermine the interior. As we can still see a tower today it is clear that Redhead was finally prevented from further demolitioning the structure.

Garrison in the Civil War

In the early stages of the English Civil War in 1642, King Charles I, fearing hostilities in London, travelled to York, bringing with him his court. For the six months following his move, York was capital of the kingdom. This led to the strengthening of the city’s defenses, with the walls being repaired and sentry boxes were built.

On August 16, the king left the city but York remained a royalist base in the North. In March of the following year, the queen, Henrietta Maria, visited York with accompanying forces and cannons aiming to maintain order in the North, once again making York a royal garrison. At the request of Queen Henrietta Maria, the building was re-roofed and floored, creating storage rooms for ammunition, and a gun-platform on the roof. The queen left York for Oxford in June 1643 with weapons and 4,500 men.

The conflict reached York the following April and despite the defensive structural work, the city fell to Parliamentarians in 1644 after numerous assaults. In 1646, the House of Commons agreed that the tower should remain occupied by a garrison. This comprised of between 40 and 80 men and was primarily used as an armoury, as records tell us that between 1650 and 1652 there were 3,000 muskets and cannnon transported to the tower.

Imprisonment of Quaker George Fox

The tower had, since it’s rebuilding between 1270 and 1290, been used as a prison, containing high-ranking prisoners and political hostages in its history.

Despite its growing dilapidation and ruinous conditions, in 1665 the Tower held the notable Quaker, George Fox, for two nights before he was transported to Scarborough Castle after spending four years of imprisonment in Dewsbury.

Fox, a campaigner against dogmatic religious and political authorities, was the founder of the Society of Friends. His ardent views resulted in his expulsion from York Minster in 1651 for preaching against the traditional church.

Fire and Neglect

By the late 17th century the Tower was becoming increasingly derelict due to the neglect and degenerate behaviour of the garrison. In 1683 a survey of the tower and castle's defensive capabilities. The result of this survey suggested that the tower and castle should be degarrisoned, an opinion that was shared by the local population who drunk toasts to 'the demolition of the Minced Pie', which is how the tower had come to be known.

It is thought that this escalated in April 1684 when the firing of a ceremonial salute for Saint George’s Day from the top of the tower resulted in a fire that destroyed part of the building and possibly the roof, as a contemporary sketch of the interior by Francis Place displays a completely roofless tower.

Although the tower was not totally ruinous, its structure was increasingly compromised and by the early 18th century it was released to freeholders and no longer housed ammunition but instead provided shelter for cattle. It was a distinctly different building to what it had once been, and newly built courthouses and gaol buildings in the 1820s and 30s only excluded it further, enclosing it within the castle complex and obscuring it from view.

Executions and Prison Complex

The York Tyburn was an area to the south of the city, now part of York Racecourse, that functioned as one of four execution sites in York. For four centuries it hosted public executions, claiming the lives of many notable criminals, including the infamous highwayman, Richard “Dick” Turpin.

Turpin had been travelling under the assumed name of John Palmer when he was arrested at a Yorkshire inn for burglary, horse theft, and murder. He had aroused suspicion when local magistrates questioned how he made his money. Then, once imprisoned at York Castle, he wrote a letter to his brother and was identified as Turpin by his handwriting. He was found guilty and executed at the Knavesmire on 7th APril, 1739.

Executions took place at these sites until 1801 when a Tyburn, or gallows, was permanently erected at the Castle Prison. From this date onwards all executions were administered by the Castle Prison on their grounds and accessible to the public.

The lay-out of the castle complex at that time consisted of the Eye of York, a grassed area surrounded by three buildings. These buildings were the Assize Courts of 1773-77, a Female Prison that was constructed between 1780 and 1783, and the Debtors’ Prison, built between 1701 and 1705 and described by Daniel Defoe as "the most stately and complete of any in the kingdom, if not in Europe".

The most notable execution that took place in the castle complex was that of Mary Bateman, also known as "The Yorkshire Witch". Convicted of murder by poisoning in May 1808, Mary was hanged on March 20th, 1809, and her body was displayed in public. Thousands of people paid to view her corpse and the proceeds of this public display were given to charity, with strips of her skin sold as charms to ward off evil.

The Eye of York: Political centre

York's location meant that it became a main political centre for the three Ridings and the site of political hustings, electing members of parliament for York. It was for this reason that it was given the title, the Eye of the Ridings, which would eventually become more popularly know to us as the Eye of York or Castle Green.

It was first created in 1777 when the castle courtyard was grassed over to form the oval lawn that exists today. It's relevance as a political centre, flanked by the castle complex, is identifiable by the notable events that took place there.

It was here that the politician William Wilberforce delivered a powerful and influential speech at the Yorkshire county meeting in 1784. Aged just 24, Wilberforce spoke for over an hour to those gathered at the site. James Boswell, the Scottish writer described the event: “I saw what seemed a mere shrimp mount upon the table; but as I listened, he grew and grew, until the shrimp became a whale”. The following day, Wilberforce returned to the Eye of the Ridings and was elected MP for Yorkshire.

On 16th October 1832, Richard Oastler, a leading man in the fight for a ten hour day for children employed in factory work, organised a march to the political centre of York. His campaign and letter to the Leeds Mercury calling for a ten hour day generated enormous support from people across the region. Over 20,000 people from the towns and villages of the West Riding made their way towards the Eye of the Ridings in protest of the ill treatment and disgraceful working conditions that children endured.

Execution of Luddites in 1813

In January 1813, a number of Luddites, men who had been protesting the introduction of labour-replacing machinery, were imprisoned, tried, and executed at York Castle.

The trials took place between 2nd and 16th January, and the first executions on Friday 8th January. The men that were executed on that day were George Mellor, William Thorpe and Thomas Smith. These were the first of 17 men to be hanged in the castle complex. The bodies of these men were taken to the County Hospital for dissection and the body parts dispersed.

Further executions were carried out in two lots, with fourteen men hanged on Saturday 16th January. Unlike Mellor, Thorpe, and Smith, the bodies of these men were given to the families to be carried on carts in a procession back to their homesteads in the Pennines. 7 other men had their death penalties commuted to transportation.

Ruined and Restored

From the 17th century to the 19th century, the structural integrity of Clifford’s Tower steadily declined. Then, in 1902, a renewed campaign of repairs and research was undertaken by renowned civil engineer Basil Mott. His work on the tower included a partial reconstruction of the mound, underpinning the south-east lobe with buried concrete ‘flying buttresses’ to keep the tower walls upright. It was during Mott’s works that the most detailed archaeological investigation to-date was carried out on the internal structure of the mound that surrounds and supports the tower.

On 30 March 1915, Clifford’s Tower was taken into state guardianship and by 1935 it had been repaired with the addition of greater pubic access. The prison buildings dating from the 19th century, including the wall enclosing the mound, were demolished and the lower parts of the slope restored to what is belived to be their original medieval profile. A new stairway leading up to the tower was also included, replacing a spiral path.

The illustration shows the massive house for the prison governor, prior to its demolition in 1935. Clifford's Tower can be seen behind. In 1900 the male prison was made available to the War office for use as a military prison. This was closed in 1929 and ceased to be a prison at all in 1932. The building materials from the demolition were available for purchase. Stones from the walls were probably added to the mound because it is in this era that the mound changed shape, increasing in size.

First World War Enemy Aliens Encampment

Although the tower was not in good repair from the 1680s onwards it may have sometimes been used as a prison, with the room above the gateway (the chapel) offering cell accommodation where perhaps the Quaker George Fox was imprisoned in the "high dungeon".

But what is for certain, is that with the building of the prisons in the surrounding complex of the Castle, the larger footprint of the Castle still interned prisoners. In 1900 the 'male' prison was made available to the War Office for use as a military prison which explains the photograph of tented prisoners. During the First World War when this picture was taken, the Eye-of-York, the grassed area of land in front of the tower, was used as an interment camp for people considered by the government to be “enemy aliens”.

Do read more about the 'Enemy Alien' encampment at Castle Green & listen to the BBC Radio Feature produced by Historyworks here:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0230mnb

Youtube & Scripts: York Jewish History Trail by IPUP Interns

This leaflet and audio tour are the product of a research project organised by Helen Weinstein, founding Director of the Institute for the Public Understanding of the Past (IPUP), working in partnership with the City Archaeologist, John Oxley. It was conducted and implemented by IPUP Interns who were postgraduate students from the University of York: Jon Cook, Hannah Lyons, Daphne Mayer, Alex O'Donnell, Tom Sutton, Bill White, and Ben Wilkinson.

Read by John Oxley.

Graphics created by Ross Casswell of Historyworks.

Script as a PDF